This blog was initially published by our partner, the RANE network: https://www.ranenetwork.com/rane-blog/buffering-against-climate-risk-lessons-for-the-refugee-crisis/

As the world watches countless economic migrants and war refugees journey perilously from their volatile homelands to relatively stable countries that respond with tactics as varied as their histories, two overarching questions arise: How did we arrive at this stage of human suffering? And what can we do to avoid it from occurring again?

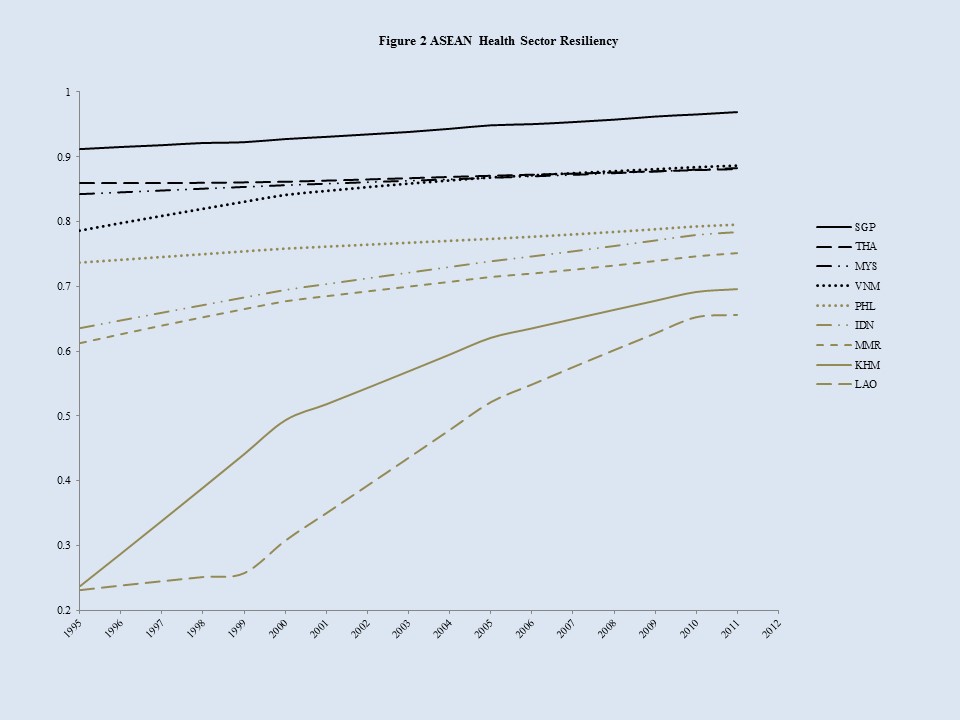

I think it is worth examining why some countries withstand stress while others don’t. In my work with the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Index, I focus on how countries adapt to the stresses and shocks of climate change. I think there are valuable lessons from this examination of climate risks to help explain why some countries are buffered from creating refuges when times get tough.

In ND-GAIN’s country index, we identify those countries that have significantly improved their economic, social or governance components (which we examine as a way to understand a country’s readiness to take on adaptation investment) and have decreased their climate vulnerability over the past two decades

There is a unique set of 10 countries who have decreased their vulnerability and increased their readiness more over the last 20 years.

While this set of countries seem more diverse than similar – different locations, government type, history and economic systems, these countries share common features, and one in particular stands out from the 46 indicators ND-GAIN examines: political stability. It turns out that the stability afforded by good governance in the form of political stability may buffering them from stress turning to crisis in the case of both climate risk and emigration.

It is interesting to examine the diversity in these countries’ approach to gaining political stability. The countries can be categorized into three groups: those who improved, those who worsened but then rebuilt and those who remained mostly unchanged.

In the first group are Rwanda, Angola, Georgia and Turkey. Each has improved its political stability since 1995. Rwanda and Angola, for instance, have made significant peacekeeping strides from their violent past of civil wars and genocides. Human rights have improved there, too.

The group of countries whose political stability worsened but then rebounded includes Saudi Arabia, Belarus and Oman. Saudi Arabia’s leader suffered a stroke, which led to an odd period of leadership. The war in Iraq and al-Qaeda’s presence in the region also affected it and led to decreased political stability. Since, however, the Saudi government has retained some of its lost political stability, which helps it prepare for climate change.

Oman also suffered from events in Iraq but made great progress since in its elections and freedoms. Belarus, which gained independence in 1991 from the Soviet Union but then endured abusive authoritarian rule, regained political stability after its people protested.

Those countries that remained mostly politically stable in the past 20 years include Uruguay, Mauritius and the United Arab Emirates. While they experienced quite a bit of change during this period, they dealt with it within their current political system, and this has led to their success in climate change preparedness.

As Rockefeller Foundation President Judith Rodin notes, “… it’s what doesn’t happen that proves success. When disruptions do not become disasters, we’ve won. When a community is resilient and stays strong in the face of a crisis, (we) mark a victory.”

These 10 countries, then, may well hold lessons to today’s heart-breaking emigration from Syria and elsewhere. In the 10, we see political stability as a buffer to the shocks and stresses of climate change — and perhaps as well to the tragedy of exodus from them.

Countries whose vulnerability to climate change, other global challenges decreased while readiness to improve resilience improved. (Top 10 out of 182)

| Country |

ND-GAIN Country Index Score Improvement 1995-2013 |

| United Arab Emirates |

16.06 |

| Saudi Arabia |

13.98 |

| Turkey |

12.56 |

| Rwanda |

12.24 |

| Oman |

12.04 |

| Georgia |

11.23 |

| Mauritius |

11.11 |

| Angola |

10.85 |

| Uruguay |

10.65 |

| Belarus |

10.56 |

Joyce Coffee is managing director of the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Index (ND-GAIN).

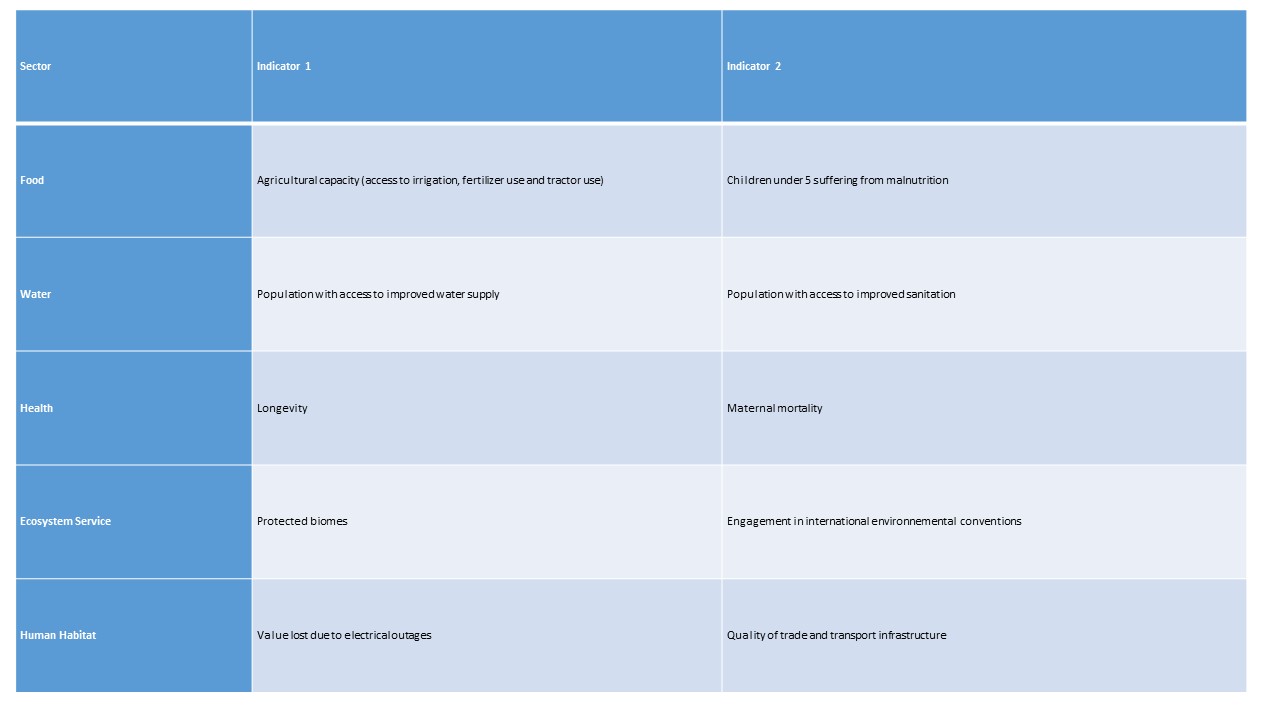

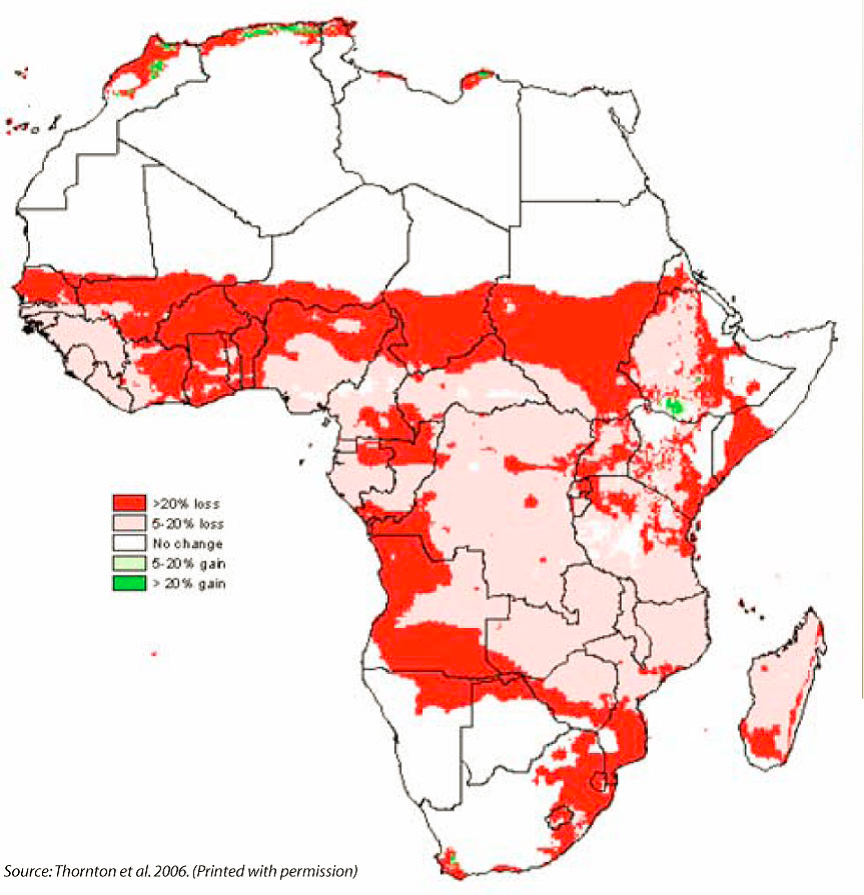

To measure countries’ resilience to rebound from adverse impacts of climate change, ND-GAIN focuses on the adaptive capacities of five sectors that provide communities with life-supporting assets and social services:

To measure countries’ resilience to rebound from adverse impacts of climate change, ND-GAIN focuses on the adaptive capacities of five sectors that provide communities with life-supporting assets and social services: